Not that long ago number theory was considered strictly pure math. Then came applications to cryptography. Now number theory is at the foundation of the online economy.

What are the next areas of pure math to find widespread application? Some people are saying algebraic topology and category theory.

[I saw a cartoon to this effect the other day but I can’t find it. If I remember correctly, someone was standing on a hill labeled “algebraic topology” and looking over at hills in the distance labeled with traditional areas of applied math. Differential equations, Fourier analysis, or things like that. If anybody can find that cartoon, please let me know.]

Algebraic topology

The big idea behind algebraic topology is to turn topological problems, which are hard, into algebraic problems, which are easier. For example, you can associate a group with a space, the fundamental group, by looking at equivalence classes of loops. If two spaces have different fundamental groups, they can’t be topologically equivalent. The converse generally isn’t true: having the same fundamental group does not prove two spaces are equivalent. There’s some loss of information going from topology to algebra, which is a good thing. As long as information you need isn’t lost, you get a simpler problem to work with.

Fundamental groups are easy to visualize, but hard to compute. Fundamental groups are the lowest dimensional case of homotopy groups, and higher dimensional homotopy groups are even harder to compute. Homology groups, on the other hand, are a little harder to visualize but much easier to compute. Applied topology, at least at this point, is applied algebraic topology, and more specifically applied homology because homology is practical to compute.

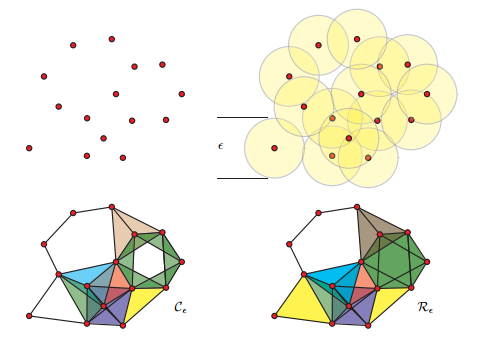

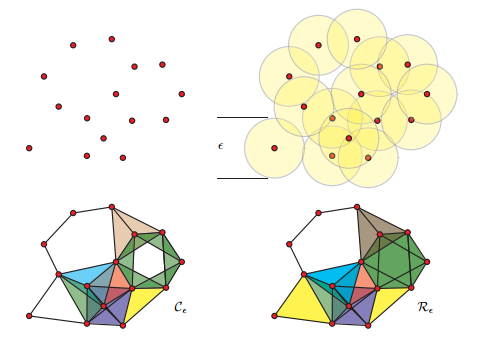

People like Robert Ghrist are using homology to study, among other things, sensor networks. You start with a point cloud, such as the location of sensors, and thicken the points until they fuse into spaces that have interesting homology. This is the basic idea of persistent homology. You’re looking for homology that persists over some range of thickening. As the amount of thickening increases, you may go through different ranges with different topology. The homology of these spaces tells you something about the structure of the underlying problem. This information might then be used as features in a machine learning algorithm. Topological invariants might prove to be useful features for classification or clustering, for example.

Most applications of topology that I’ve seen have used persistent homology. But there may be entirely different ways to apply algebraic topology that no one is looking at yet.

Category theory

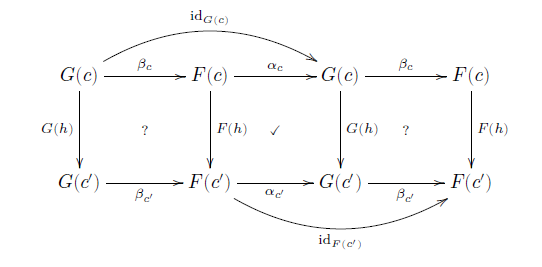

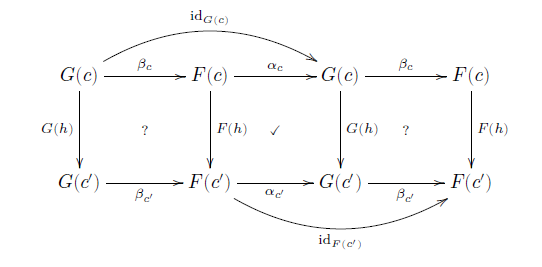

Category theory has been getting a lot of buzz, especially in computer science. One of the first ideas in category theory is to focus on how objects interact with each other, not on their internal structure. This should sound very familiar to computer scientists: focus on interface, not implementation. That suggests that category theory might be useful in computer science. Sometimes the connection between category theory and computer science is quite explicit, as in functional programming. Haskell, for example, has several ideas from category theory explicit in the language: monads, natural transformations, etc.

Outside of computer science, applications of category theory are less direct. Category theory can guide you to ask the right questions, and to avoid common errors. The mathematical term “category” was borrowed from philosophy for good reason. Mathematicians seek to avoid categorical errors, just as Aristotle and Kant did. I think of category theory as analogous to dimensional analysis in engineering or type checking in software development, a tool for finding and avoiding errors.

I used to be very skeptical of applications of category theory. I’m still skeptical, though not as much. I’ve seen category theory used as a smoke screen, and I’ve seen it put to real use. More about my experience with category theory here.

* * *

Topology illustration from Barcodes: The persistent topology of data by Robert Ghrist.

Category theory diagram from Category theory for scientists by David Spivak