I recently started reading The Case for Mars by Robert Zubrin. This post will unpack one line from that book regarding creating a calendar for Mars:

Equipartitioned months don’t work for Mars, because the planet’s orbit is elliptical, which causes the seasons to be of unequal length.

This sentence doesn’t sit well at first for a couple reasons. First, Earth’s orbit is elliptical too, and the seasons here are of roughly equal length. Second, the orbit of Mars, like the orbit of Earth, is nearly circular.

There are three reasons why Zubrin’s statement is correct, despite the objections above. The first has to do with the nature of eccentricity, and the second with the reference to which angles are measured, and the third with variable speed.

Eccentricity

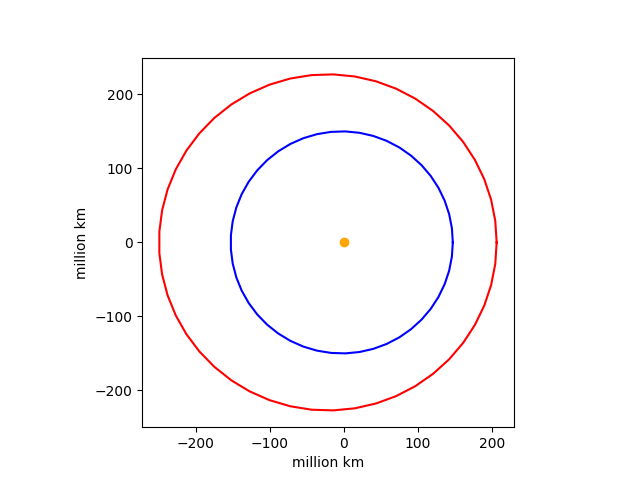

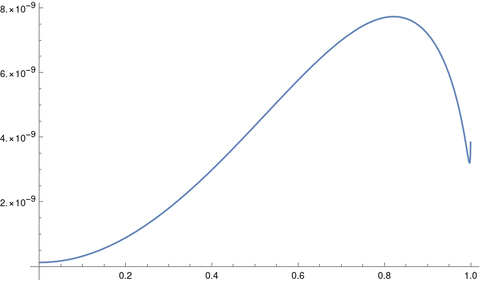

The orbit of Mars is about five and a half times as eccentric as that of Earth. That does not mean that the orbit of Mars is noticeably different from a circle, but it does mean the sun is noticeably not at the center of that (almost) circle.

There’s a kind of paradox interpreting eccentricity e. An ellipse with e = 0 is a circle, and the two foci of the ellipse coincide with the center of the circle. As e increases, the ellipse aspect ratio increases and the foci move apart. But here’s the key: the aspect ratio doesn’t change nearly as fast as the distance between the two foci changes. I’ve written more about this here and here.

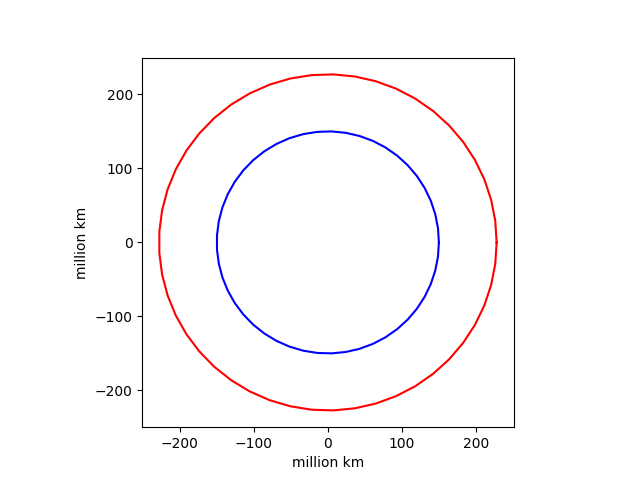

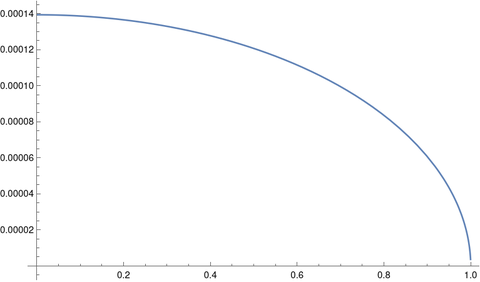

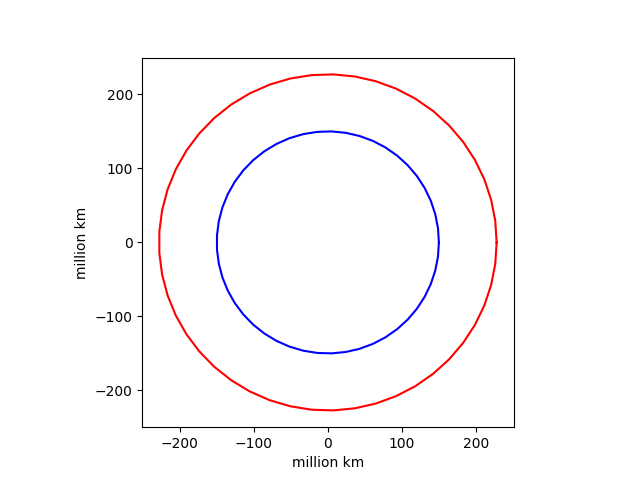

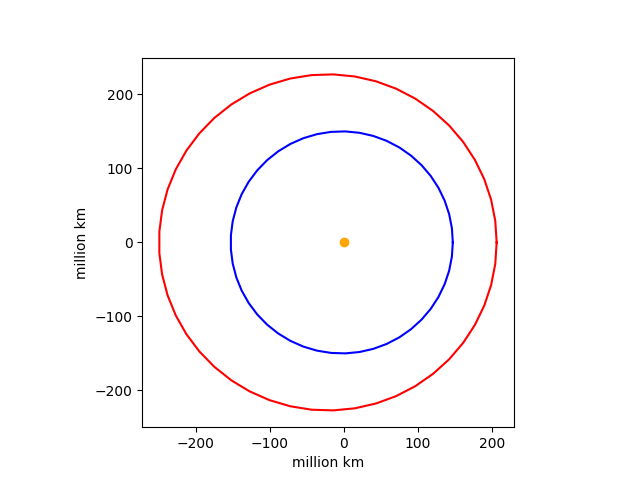

So while the orbit of Mars is nearly a circle, the sun is substantially far from the center of the orbit. We can visualize this with a couple plots. First, here are the orbits of Earth and Mars, shifted so that both have their center at the origin.

Both are visually indistinguishable from circles.

How here are the two orbits with their correct placement relative to the sun at the center.

Angle reference

Zubrin writes

In order to predict the seasons, a calendar must divite the planet’s orbit not into equal division of days , but into equal angles of travel around the sun. … a month is really 30 degrees of travel around the Sun.

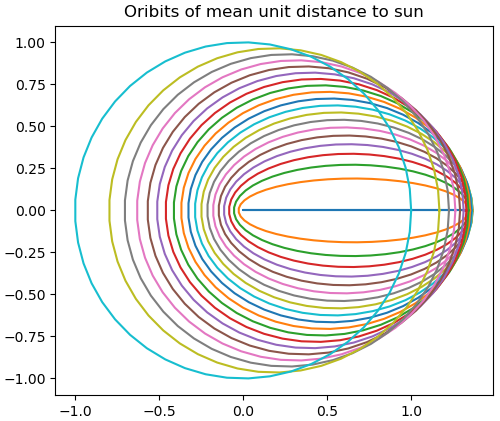

If we were to divide the orbit of Mars into partitions of 30 degrees relative to the center of the orbit then each month would be about the same length. But Zubrin is dividing the orbit into partitions of 30 degrees relative to the sun.

In the language of orbital mechanics, Zubrin’s months correspond to 30 degrees of true anomaly, not 30 degrees of mean anomaly. I explain the difference between true anomaly and mean anomaly here. That post shows that for Earth, true anomaly and mean anomaly never differ by more than 2 degrees. But for Mars, the two anomalies can differ by up to almost 19 degrees.

Variable speed

A planet in an elliptical orbit around the sun travels fastest when it is nearest the sun and slowest when it is furthest from the sun. Because Mars’s orbit is more eccentric than Earth’s, the variation in orbital speed is greater. We can calculate the ratio of the fastest speed to the slowest speed using the vis-viva equation. It works to be

(1 + e)/(1 − e).

For Earth, with eccentricity 0.0167 this ratio is about 1.03, i.e. orbital speed varies by about 3%.

For Mars, with eccentricity 0.0934 this ratio is about 1.21, i.e. orbital speed varies by about 21%.

Zubrin’s months

The time it takes for Mars to rotate on its axis is commonly called a sol, a Martian day. The Martian year is 669 sols. Zubrin’s proposed months range from 46 to 66 sols, each corresponding to 30 degrees difference in true anomaly.

Related posts