The latest episode of the Science and the Sea podcast explains how a protein that gives a certain species of jellyfish a faint glow is useful in research into cancer and other diseases.

The latest episode of the Science and the Sea podcast explains how a protein that gives a certain species of jellyfish a faint glow is useful in research into cancer and other diseases.

Everybody thinks Dilbert is about their job. But this cartoon really is about my job. It does a remarkably good job of summarizing what it’s like to work in cancer research.

Related posts on cancer research

Before I started working for a cancer center, I was not aware of the tension between science and medicine. Popular perception is that the two go together hand and glove, but that’s not always true.

Physicians are trained to use their subjective judgment and to be decisive. And for good reason: making a fairly good decision quickly is often better than making the best decision eventually. But scientists must be tentative, withhold judgment, and follow protocols.

Sometimes physician-scientists can reconcile their two roles, but sometimes they have to choose to wear one hat or the other at different times.

The physician-scientist tension is just one facet of the constant tension between treating each patient effectively and learning how to treat future patients more effectively. Sometimes the interests of current patients and future patients coincide completely, but not always.

This ethical tension is part of what makes biostatistics a separate field of statistics. In manufacturing, for example, you don’t need to balance the interests of current light bulbs and future light bulbs. If you need to destroy 1,000 light bulbs to find out how to make better bulbs in the future, no big deal. But different rules apply when experimenting on people. Clinical trials will often use statistical designs that sacrifice some statistical power in order to protect the people participating in the trial. Ethical constraints make biostatistics interesting.

When I hear of naked mole rats, I think of Rufus, the animated character from Kim Possible.

![]()

But it turns out the real rodents might be useful in cancer research. According to a recent 60-Second Science podcast, naked mole rats live in low-oxygen environments. The core of large tumors is also a low-oxygen environment, and so maybe studying naked mole rats can tell us something about cancer. So far researchers have found three genes in common between naked mole rats and cancer cells.

FermiScan, an Australian company, is developing a screen for breast cancer that analyzes a small hair sample.

Listen to Moira Gunn’s interview with David Young from FermiScan.

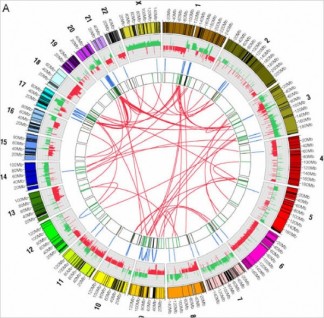

FlowingData posted this graph showing changes to the DNA of a breast cancer cell.

See the original post Researchers map chaos inside cancer cell for details.

CaringBridge offers “free, personalized websites that support and connect loved ones during critical illness, treatment and recovery.” The site is sponsored by donors, not advertising.

When he was diagnosed with cancer four years ago, a friend of mine set up a password-protected web page to let us know the latest updates on his treatment and diagnosis. I appreciated his doing this. He could easily set up his own site, but not everyone knows how to do that. CaringBridge lets people who are not as technically inclined set up their own site. Patients can upload photos, exchange messages with friends, etc. About 100,000 families have set up websites through CaringBridge so far.

Chemotherapy harms cancer cells as well as normal cells. Chemotherapy is designed to be more harmful to cancer cells than to normal cells, but the damage to normal cells can be brutal.

New studies suggest that fasting prior to receiving chemotherapy may reduce the number of normal cells harmed by the treatment. Fasting may put normal cells in a defensive mode that increases their resistance to chemical attack.

A gene therapy developed at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center for head and neck cancer is the first such treatment to succeed in a phase III trial. See the press release for more details.

(Phase III studies are large, multi-institutional studies required for regulatory approval of new drugs.)

Imagine this conversation with your doctor:

Your poor tumor. It has a chaotic blood supply. Parts of it get too much blood, other parts too little. We’re going to give you a drug to improve your tumor’s blood supply, making it healthier.

Before you run screaming from your doctor’s office, see if there’s a copy of the January 2008 issue of Scientific American in the waiting room. If there is, read the article Taming Vessels to Treat Cancer by Rakesh Jain.

Just as the cells in a tumor are abnormal and growing out of control, so are the blood vessels that feed the tumor. This lack of proper infrastructure inhibits the tumor’s growth, but it also makes it difficult to deliver chemotherapy to the tumor. This lead to the radical idea to make the tumors healthier in preparation for killing them.

So how would you go about improving a tumor’s circulatory system? By administering a drug that was designed to attack tumor vessels!

A new class of cancer drugs, antiangiogenic agents, has been designed to attack tumors by cutting off their blood supply. These agents haven’t been a complete success. Experience with one such agent, Avastin, shows that while it shuts down some of the blood vessels in tumors, it may make the remaining tumor vessels healthier. That’s bad news if you’re treating patients with Avastin alone. But when used in combination with chemotherapy, it’s just what people like Dr. Jain were looking for: a way to normalize the blood flow in a tumor in order to make it more vulnerable to chemotherapy.

More information, including videos, is available at the website of Dr. Jain’s lab.

Related: Adaptive clinical trial design