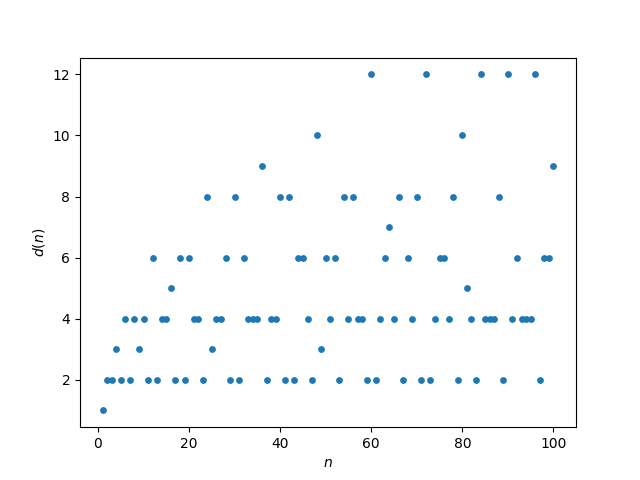

Let d(n) be the number of divisors of an integer n. For example, d(12) = 6 because 12 is divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 12.

The function d varies erratically as the following plot shows.

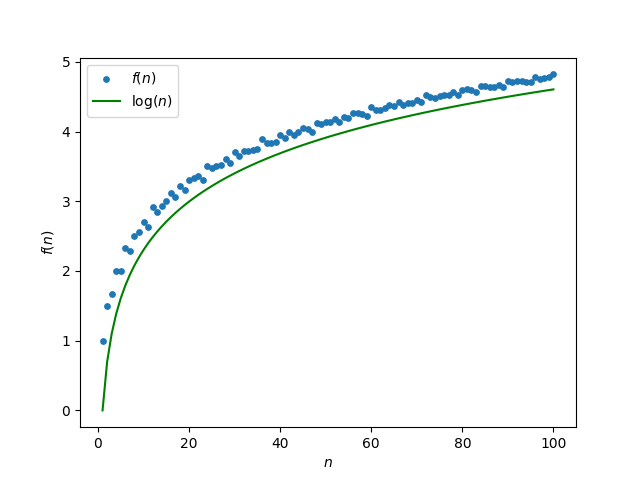

But if you take the running average of d

f(n) = (d(1) + d(2) + d(3) + … + d(n)) / n

then this function is remarkably smoother.

Not only that, the function f(n) is asymptotically equal to log(n).

Computing

Incidentally, directly computing f(n) for n = 1, 2, 3, …, N would be inefficient because most of the work in computing f(m) would be duplicated in computing f(m + 1). The inefficiency isn’t noticeable for small N but matters more as N increases. It would be more efficient to iteratively compute f(n) by

f(n + 1) = (n f(n) + d(n + 1)) / (n + 1).

Asymptotics and citations

Several people have asked for a reference for the results above. I didn’t know of one when I wrote the post, but thanks to reader input I now know that the result is due to Dirichlet. He proved that

f(n) = log(n) + 2γ − 1 + o(1).

Here γ is the Euler-Mascheroni constant.

You can find Dirichlet’s 1849 paper (in German) here. You can also find the result in Tom Apostol’s book Introduction to Analytic Number Theory.

(I thought I already wrote a comment saying this but I don’t see it. Some technical glitch somewhere, I guess? My apologies if there end up being two of these.)

A minor correction: it isn’t true that f(n) “converges to log n”, if that’s taken to mean that f(n) = log n + o(1). (It _is_ true that f(n) = log n . (1 + o(1)).)

It turns out that f(n) = log n + (2γ-1) + o(1) where γ is the Euler-Mascheroni constant (~= 0.577). So for large n, f(n) is roughly log n + 0.154.

You can see this small but persistent offset in the graph in the post — the individual data points (n, f(n)) lie above the smooth curve y = log x.

Thanks. I updated the post to say f(n) is asymptotically equal to log n rather than converges to log n. Their ratio converges to 1.