Elliptic curves are pure and applied, concrete and abstract, simple and complex.

Elliptic curves have been studied for many years by pure mathematicians with no intention to apply the results to anything outside math itself. And yet elliptic curves have become a critical part of applied cryptography.

Elliptic curves are very concrete. There are some subtleties in the definition—more on that in a moment—but they’re essentially the set of points satisfying a simple equation. And yet a lot of extremely abstract mathematics has been developed out of necessity to study these simple objects. And while the objects are in some sense simple, the questions that people naturally ask about them are far from simple.

Preliminary definition

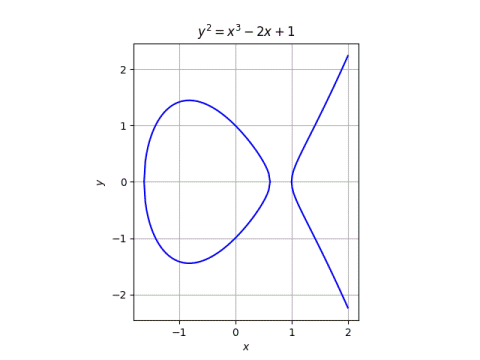

A preliminary definition of an elliptic curve is the set of points satisfying

y² = x³ + ax + b.

This is a theorem, not a definition, and it requires some qualifications. The values x, y, a, and b come from some field, and that field is an important part of the definition of an elliptic curve. If that field is the real numbers, then all elliptic curves do have the form above, known as the Weierstrass form. For fields of characteristic 2 or 3, the Weierstrass form isn’t general enough. Also, we require that

4a³ + 27b² ≠ 0.

The other day I wrote about Curve1174, a particular elliptic curve used in cryptography. The points on this curve satisfy

x² + y² = 1 – 1174 x² y²

This equation does not specify an elliptic curve if we’re working over real numbers. But Curve1174 is defined over the integers modulo p = 2251 – 9. There it is an elliptic curve. It is equivalent to a curve in Weierstrass form, though that’s not true when working over the reals. So whether an equation defines an elliptic curve depends on the field the xs and ys come from.

Not an ellipse, not a curve

An elliptic curve is not an ellipse, and it may not be a curve in the usual sense.

There is a connection between elliptic curves and ellipses, but it’s indirect. Elliptic curves are related to the integrals you would write down to find the length of a portion of an ellipse.

Working over the real numbers, an elliptic curve is a curve in the geometric sense. Working over a finite field, an elliptic curve is a discrete set of points, not a continuum. Working over the complex numbers, an elliptic curve is a two-dimensional surface. The name “curve” is extended by analogy to elliptic curves over general fields.

Final definition

In this section we’ll give the full definition of an algebraic curve, though we’ll be deliberately vague about some of the details.

The definition of an elliptic curve is not in terms of equations of a particular form. It says an elliptic curve is a

- smooth,

- projective,

- algebraic curve,

- of genus one,

- having a specified point O.

Working over real numbers, smoothness can be specified in terms of derivatives. But what does smoothness mean working over a finite field? You take the derivative equations from the real case and extend them by analogy to other fields. You can “differentiate” polynomials in settings where you can’t take limits by defining derivatives algebraically. (The condition 4a³ + 27b² ≠ 0 above is to guarantee smoothness.)

Informally, projective means we add “points at infinity” as necessary to make things more consistent. Formally, we’re not actually working with pairs of coordinates (x, y) but equivalence classes of triples of coordinates (x, y, z). You can usually think in terms of pairs of values, but the extra value is there when you need it to deal with points at infinity. More on that here.

An algebraic curve is the set of points satisfying a polynomial equation.

The genus of an algebraic curve is roughly the number of holes it has. Over the complex numbers, the genus of an algebraic curve really is the number of holes. As with so many ideas in algebra, a theorem from a familiar context is taken as a definition in a more general context.

The specified point O, often the point at infinity, is the location of the identity element for the group addition. In the post on Curve1174, we go into the addition in detail, and the zero point is (0, 1).

In elliptic curve cryptography, it’s necessary to specify another point, a base point, which is the generator for a subgroup. This post gives an example, specifying the base point on secp256k1, a curve used in the implementation of Bitcoin.

After many years (I am now 75) I am going back to graduate school to finish my PhD in mathematics. I am currently studying for a prelim in complex Analysis. Thank you for your help.

That’s fantastic!

I’m 35, pursuing a career change from Education to cybersecurity and encryption is something that really piques my interest (conceptually) and the thought (now four years on from this post) that quantum computing is not too far away (although much further from a public use-realm than it is from being implemented in laboratories etc.) is quite a terrifying one – thinking of the use case if it gets into the wrong hands, for instance. I’m thankful for people who specialize in, and dedicate their skills and knowledge to, this realm.

Thanks, John!

PS: I hope that everything went (or is going) well with finishing your PhD, Mr Geistfeld (or is it Dr now?)