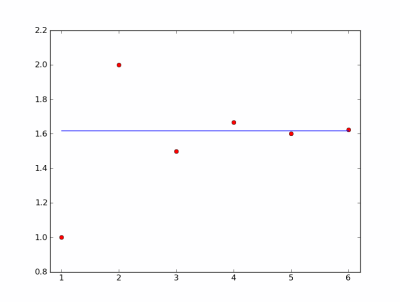

You may know that ratios of consecutive Fibonacci numbers tend to the golden ratio in the limit. But do know how they tend to the limit? The ratio oscillates, one above the golden ratio, the next below, each getting closer. The plot shows F(n + 1) / F(n) where F(n) is the nth Fibonacci number. The height of the horizontal line is the golden ratio.

We can prove that the ratio oscillates by starting with the formula

![]()

where φ = (1 + √5)/2 is the golden ratio.

From there we can work out that

![]()

This shows that when n is odd, F(n + 1) / F(n) is below the golden ratio and when n is even it is above. It also shows that the absolute error in approximating the golden ratio by F(n + 1) / F(n) goes down by a factor of about φ2 each time n increases by 1.

The first two terms of the traditional Fibonacci sequence starts with the values 1, 1. As you’ve shown, the ratio of successive terms of the Fibonacci sequence converge to the golden ratio.

But did you know that you can start the sequence with ALMOST ANY two numbers, apply the Fibonacci recurrence relation, and the ratio of successive terms STILL converges to the golden ratio? And furthermore the ratio still oscillates above and below, as you’ve described. For the explanation and a picture of this phenomenon, see the article “Matrices, eigenvalues, Fibonacci, and the golden ratio” at my blog.

If one generalizes the ratio result a bit, you can find an interesting

asymmetric-looking addition formula:

F(n+m) = F(n)phi^m + F(m) (-1)^n phi^(-n)

Whenever I see something proven with the absolute formula of the Fibonaccis I always try to think about the proof that comes directly from the recursive relationship.

In this case if you have r_n = F(n+1)/F(n) then you get pretty quickly that r_n = 1 + r_{n-1}^{-1}

We know that phi satisfies the relationship phi = 1 + phi^{-1}

So if 0<r_{n-1} phi^{-1} and so

r_n = 1 + r_{n-1}^{-1} > 1 + phi^{-1} = phi

And similarly for the converse case.

You don’t get your lemma, or even convergence. But you do get oscillation.

Oops, html thinks I’m making a tag phi tag.

I meant

So if

0 < r_{n-1} phi^{-1}

and so

sigh. I’m no good at this

I mean

if r_{n-1} is less than phi and greater than 0 then the inverse of r_{n-1} is greater than the inverse of phi

and so…

John, feel free to delete and alter my comments to remove the mess I’ve made.

The way this works is really nicely expressed when you look at it in terms of continued fractions. Then the properties of continued fractions explain why the sequence of approximations alternates between under- and over- approximation.