Lilypond is a TeX-like typesetting language for sheet music. I’ve had good results asking AI to generate Lilypond code, which is surprising given the obscurity of the language. There can’t be that much publicly available Lilypond code to train on.

I’ve mostly generated Lilypond code for posts related to music theory, such as the post on the James Bond chord. I was curious how well AI would work if I uploaded an image of sheet music and asked it to produce corresponding Lilypond code.

In a nutshell, the results were hilariously bad as far as the sheet music produced. But Grok did a good job of recognizing the source of the clips.

Test images

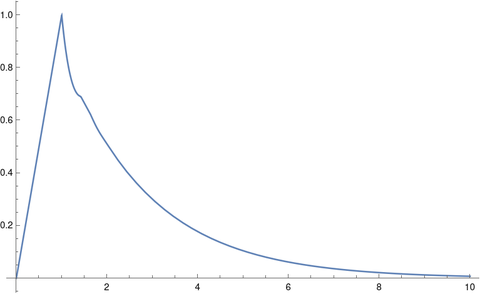

Here are the two images I used, one of classical music

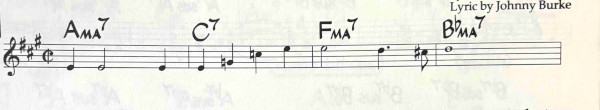

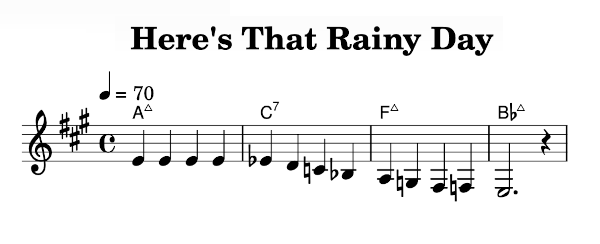

and one of jazz.

I used the same prompt for both images with Grok and ChatGPT: Write Lilypond code corresponding to the attached sheet music image.

Classical results

Grok

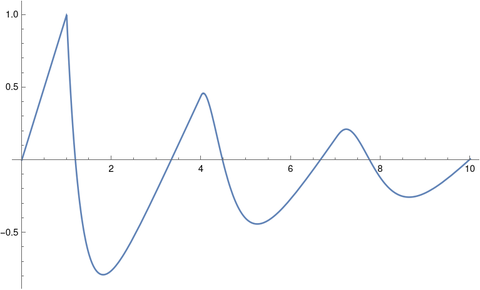

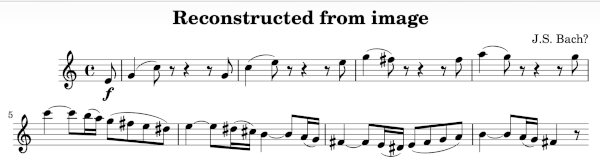

Here’s what I got when I compiled the code Grok generated for the first image.

This bears no resemblance to the original, turning one measure into eight. However, Grok correctly inferred that the excerpt was by Bach, and the music it composed (!) is in the style of Bach, though it is not at all what I asked for.

ChatGPT

Here’s the corresponding output from ChatGPT.

Not only did ChatGPT hallucinate, it hallucinated in two-part harmony!

Jazz results

One reason I wanted to try a jazz example was to see what would happen with the chord symbols.

Grok

Here’s what Grok did with the second sheet music image.

The notes are almost unrelated to the original, though the chords are correct. The only difference is that Grok uses the notation Δ for a major 7th chord; both notations are common. And Grok correctly inferred the title of the song.

I edited the image above. I didn’t change any notes, but I moved the title to center it over the music. I also cut out the music and lyrics credits to make the image fit on the page easier. Grok correctly credited Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen for the lyrics and music.

ChatGPT

Here’s what I got when I compiled the Lilypond code that ChatGPT produced. The chords are correct, as above. The notes bear some similarity to the original, though ChatGPT took the liberty of changing the key and the time signature, and the last measure has seven and a half beats.

ChatGPT did not speculate on the origin of the clip, but when I asked “What song is this music from?” it responded with “The fragment appears to be from the jazz standard ‘Misty.'”